Lost Worlds

When past and future clash

We slowly made our way from Palenque to the Calakmul Biosphere, a large protected jungle that bleeds all the way into Guatemala. The remoteness of this area and its ancient ruins were making it even more intriguing for us to visit. The road into Calakmul is long and narrow. We had read about a handful of wild camping options within the biosphere and after some discussion at the first gate, we managed to enter; trailer, pets and all. We squeezed into our unofficial (but not illegal!) camp spot at the end of a little dirt road close to the second gate, the entrance to the ruins, and marveled in the wildness of the place.

Within a few hours the last visitors would leave and there would be nobody around for miles and miles. Nothing but thick jungle between us and the border to Guatemala.

Our efforts and dedication were immediately rewarded when we heard some cracklings in the surrounding bushes. First one, then three, and eventually a whole pack of coatimundis surrounded our little camp. At dusk we were paid a visit by a handful of bats, and late at night we could hear howler monkeys in the distance. The next morning we disconnected the truck and left our pets in the shaded trailer while making our way towards the ruins. Even though we were already close to the second entrance, the whole drive took more than an hour. Luckily we got there fairly early and were able to enjoy and climb the ancient ruins with only a few other early birds around.

With an estimated population of 50.000, Calakmul was one of the largest cities in the Maya Lowlands. It's ongoing rivalries and wars over resources and dominance with Tikal and Palenque are at the heart of Classical Maya history. Even though its early history is unclear, it is believed that Calakmul was established between 700-350 BC, peaked in the 7th century, and was then gradually abandoned in the 9th and 10th century. It's modern name translates to 'The City of the Two Adjacent Pyramids'.

The main pyramid is indeed massive, with its 160 ft reaching far over the treetops, and a small temple and fantastic view at the top. Some areas were not accessible at the time, but beyond that visitors are free to roam and climb as they wish. Our legs were still burning the next day! The site, with large trees growing out of walls and buildings, roaming ocellated turkeys, coatimundis, and several kinds of monkeys playing high up in the trees, is truly a magnificent place to visit and even though we did not see any jaguars, knowing that they are around added much excitement to our stay there.

We had planned on making several stops along the coast, between Chetumal and Playa del Carmen, south of Cancun. White beaches, turquoise water, and five star resorts have earned the Riviera Maya the nickname ‘the Philippines of Mexico’. We spent a few quiet nights at a little lagoon outside of Chetumal and quickly passed through Bacalar and Tulum. In Tulum you will find ancient ruins, world famous cenotes, and the obligatory Starbucks next to a line of souvenir shops.

Little did we know then that this buzzing town would soon make the headlines, with tourists getting stranded after three hotels were evicted due to land disputes.

Finding the whole area a little over prized and over developed, basically a Disneyland version of Mexico, we turned inland along the 'ruta de los cenotes'. While driving we noticed long stretches of forest being cut down and bulldozed over, the first but not last signs of the Maya Train to come.

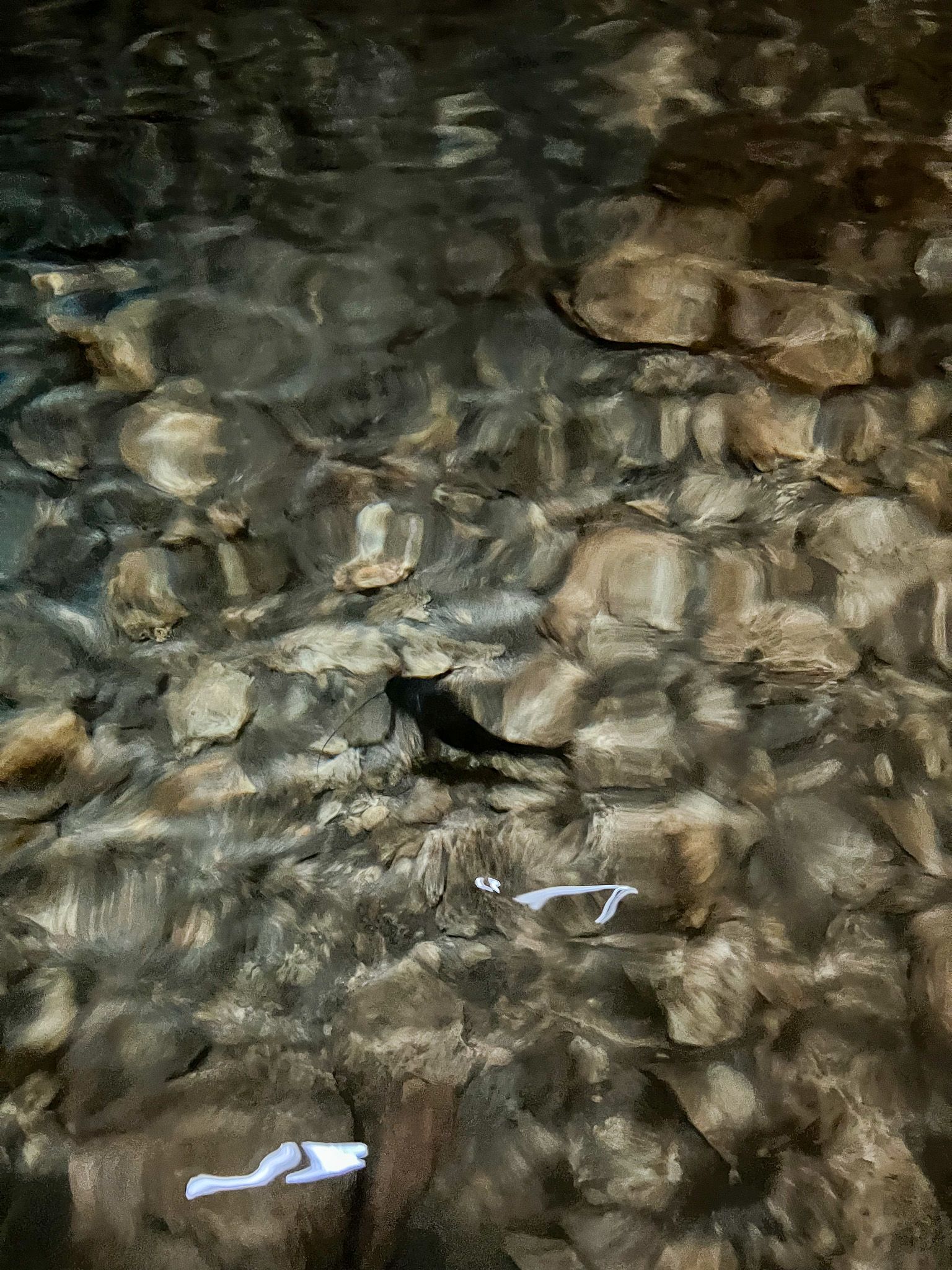

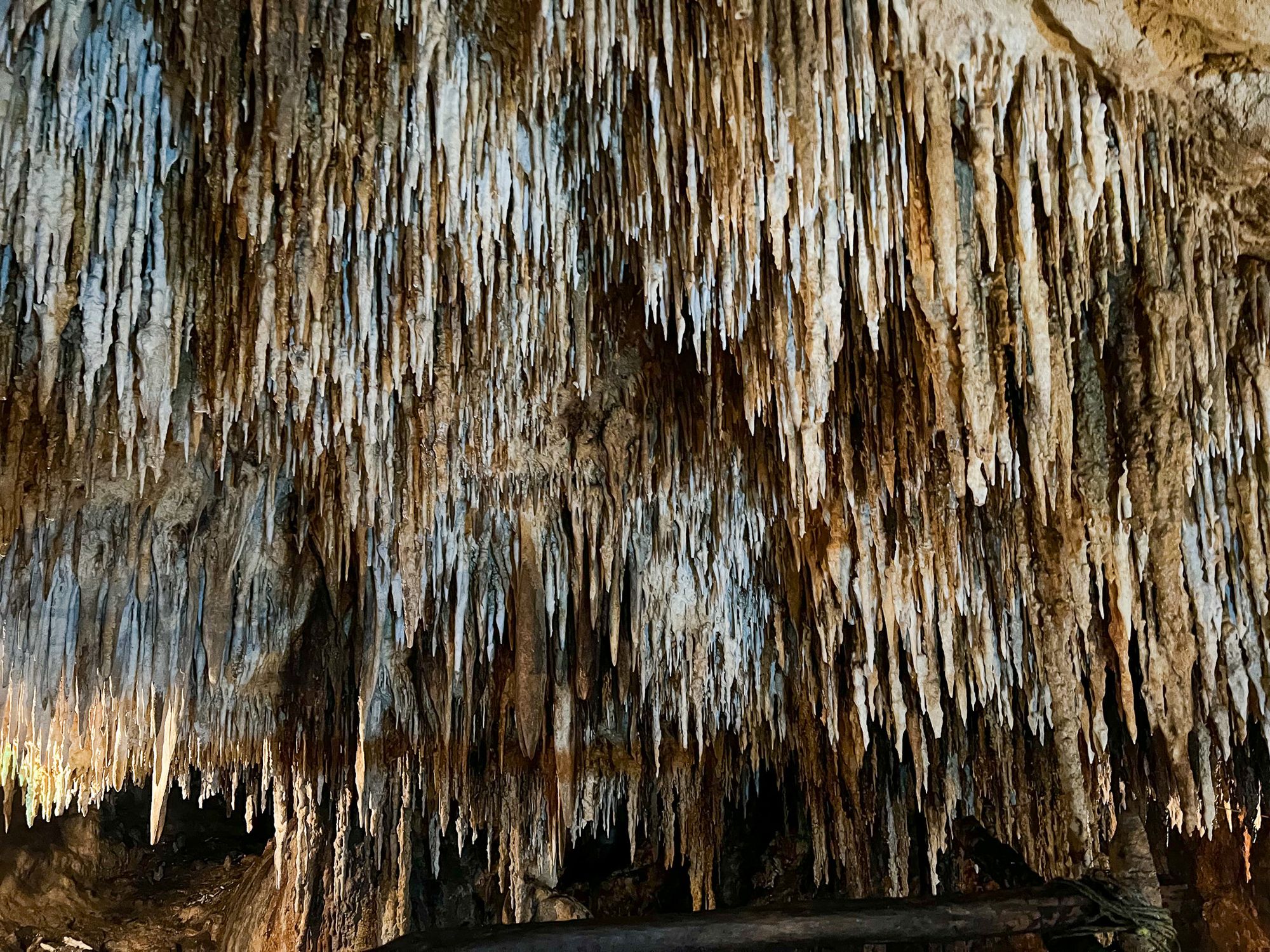

When we arrived at our next camp spot we quickly realized that our hosts, an adventurous German couple, former long term backpackers, and now in the middle of building their own campground and Airbnb igloo, had come upon something very special: an underground cave with stalactites, fresh water, and as the Maya believed, their private entrance to the underworld. We took a dip in this still unexplored cenote, turned the lights off, and listened to the rain trickling in.

There are an estimated 10,000 cenotes spread all over the Yucatan and Quintana Roo peninsula, with many still unearthed and undiscovered. Underlying porous limestone lets rain water trickle through which, over time, dissolves layers of stone, and thus slowly carves out interconnected cave systems and sinkholes. Since the porous ground does not allow for the development of rivers and lakes, cenotes were regularly used by the Maya for fresh water storage and also served as ritualistic sites. Explorations into the underground cave systems have produced a multitude of priceless artifacts, some of which have become protected by the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. These ancient and prehistoric time capsules have given archaeologists and historians insights not only into Maya culture but also into prehistoric developments, with the findings of several human remains and even a mastodon.

But the origin of cenotes goes back even further than that. The predominant theory explains their existence as a result of the asteroid impact 65 million years ago that created the Chicxulub crater and led to the mass extinction of large dinosaurs. The subsequent ripple effect led to tsunamis, a drastic change in the earth’s atmosphere, and what is today known as the ‘ring of cenotes’, an almost perfect 112 mile wide arch around the center of the crater. The impact of the asteroid, even though underground, can still be seen via satellite view. Before impact the whole peninsula was still an underwater coral reef, as can be seen from the levels of seashells that make up the walls of some cenotes. In fact, the second cenote we visited gave us a glimpse into this lost world, with rooms full of stalactites, stalagmites, and walls layered with seashells.

If you like you can even take a deep dive and explore the interconnected underwater cave systems of some cenotes. That is, as long as they have not yet collapsed. Archaeologists are racing the clock as we speak, trying to find and rank the peninsular's most important historical sites. What doesn't make the cut, will probably be sacrificed to the new developing infrastructure system, the Maya Tren, an ambitious project which will loop around the whole peninsular and thereby connect popular beach town resorts like Cancun, Tulum, and Bacalar, with large cities such as Mérida and ancient historical sites like Calakmul and Palenque.

The train was promised to be environmental friendly, with a grotesque ceremony at its official announcement in 2018, asking for Mother Nature's permission to build the train. The new infrastructure is also supposed to bring education and prosperity to Mexico's poorest states. However, it is highly questionable whether Mother Nature would give her blessing to biospheres being slashed through, rain forests getting cut down, bulldozed over, and the habitat and hunting grounds of already endangered species being cut in half. Besides that, many of the promises made back then have already been broken. The costs have tripled, plans were changed mid construction after the damage was done, and caves have already collapsed.

Recent history in Cancun, Tulum, and Chiapas also tells a very different story in how far the benefits of large scale tourism projects actually trickle down to the native inhabitants. In 2022 Cancun made headlines for hotels being evicted due to unpaid wages and unfair dismissals. Several civil court cases over land disputes in Tulum have left tourists stranded after their hotels were suddenly, and at times violently, evicted. The ongoing roadblocks between San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque are reminiscent of the suppression of indigenous people and show how little native people gain from their regional popular tourist attractions.

If the train gets finished, it will undoubtedly make hard to reach areas more accessible. This begs the question, how much convenience do travelers (and guests in foreign countries) really need and deserve? Isn’t being uncomfortable and dealing with the unknown part of the excitement in traveling? Isn’t there reward in adventure, and doesn’t that entail at least some kind of inconvenience? Can we justify irreparable destruction of nature and possibly undiscovered archaeological sites with arguments of accessibility and comfort? It's unquestionable that our experience in Mexico, in particular of the southern peninsula was an intimate look into a region that holds so much mystery that will be lost once the march of development progresses.