Unlikely Sisters: Sacred Water and Vanishing Land

I recently returned from a 2 week trip to New Orleans, and with my bags hardly unpacked, we were getting ready to head out again for a 10 day work trip to Taos. While reading up on Taos' history, it got me thinking. I had planned to write about New Orleans several times over the last two years, but once I got there, the right words never emerged and writing about something that feels so much larger than life often seems to minimize it, demagnify its grandeur, and demystify all the things I love about it.

It is true what people say: Some places are like people. To love them means to know them fervently, and to leave them means to miss them, the way you would miss a good friend. Some places are also too big to write about by themselves, too complex, interconnected, and ever shifting. Like Calvino’s Venice in Invisible Cities, New Orleans is a mirage and can only be seen from a distance and through the lens of other places. Maybe it even became the lens that tints every other place I go to.

Some of my favorite spots in New Orleans: Rusty Rainbow, Angelo Brocato, Suis generis, the end of the world seen from Holy cross, backyard BBQ and crawfish boil

Unlikely sisters

In some ways, Taos and New Orleans could not be more unlike: one, a high elevation desert town and ski resort at 7,000 ft, with cacti, piñons, long snowy winters, and the eerie sound of coyotes at night. The other, a subtropical harbor and party city, with palm trees, mossy live oaks (a pure magnet for hopeless romantics like me), steamy summers, and alligators floating lazily in the mucky bayou waters. With its elevation partly below sea level, New Orleans might slowly turn into a second Venice, with water filled canals for streets.

Despite their differences, both cities are undoubtedly fueled by a certain mystic energy! In Taos, the famous mountain sits enthroned over the town, and people in Taos seem to talk about the mountain the way I talk about the temperamental river gods in New Orleans: Sometimes they favor you with seemingly endless gifts, and sometimes they test your commitment to the city. In Taos the mountain either accepts and claims you, or it rejects you, and you better get out of there fast!

The mysterious Taos Hum has been the topic of many theories and investigations, the elusive quality of the light has attracted many painters over the last century, and the fabled but forbidden Blue Lake is now off limits to tourists. In New Orleans, the French quarter is full of vampire, pirate, and ghost stories, and Lafayette square is packed with palm and tarot readers, ready to tell you your fortune. I should have asked the fortune teller more questions back when I first came to New Orleans. Turned out she was right. I still get my cards read remotely from time to time, by my long term go-to reiki master and later landlord, who now lives in Alabama.

Rebellious sisters from another mother

While I’m reading the article Deeply Rooted by David Gomez, about growing up in Taos, I realize that his wife Inez works with Michael and I have sat next to her and chatted with her several times. So much for interconnected communities. He talks about coming back to Taos to chop wood for his family for the winter, and about getting a chicharron burrito with red chile at the drive through of Mante’s Chow cart.

Locals usually don’t tend to do the tourist attractions, or traps, that cities are often famous for. I try to avoid Mardi Gras and Jazz Fest, when I go back to visit friends. However, I often aim for French Quarter Fest, so I can see my friends perform. I try to hit my favorite, sometimes hole in the wall (or fence) neighborhood spots, like Suis generis, Rosalita’s, Angelo Brocato, N7, and Budsi’s. Instead of French quarter bars, there are backyard bbqs with bonfires and pop up concerts at ominous locations like ‘under the bridge’, at ‘the Pearl’, ‘L13’, ‘at the end of the world’, or ‘the fence behind the Quickies’. Half of those places sadly don’t exist anymore. For the downtown crowd, there are spontaneous late night meet ups at Hanks, a 24/7 liquor store on St Claude, where everybody gets their fried chicken on their way home. That is, before the security guy shot someone and everybody started boycotting it (for a while). When I go back to visit friends, I sometimes feel like the New Orleans I fell in love with a few years ago doesn't exist anymore. So many places have permanently closed, friends have moved, apartment complexes have sprung up in historic and previously infamous neighborhoods. At least Hanks will still be there for a while.

NOMA, Dasher enjoying the local bar scene, Marigny neighborhood, New Orleans

Besides their mystical qualities, those two unlikely sisters have other things in common. Both are famous for their unique and distinct historical style of architecture. One, classic earthen colored adobe style houses, the other a wild mix of Creole style French, Spanish, and Caribbean elements, and Classic- and Greek Revival architecture, that come in the forms of cottages, shotguns and mansions. While both cities try to preserve the pure aspect of their historic town centers, there is also a clear, quirky, anything goes attitude, that can be seen in colorfully painted houses and cars, garden arrangements, and of course, the world famous Earthships just outside of Taos.

Downtown New Orleans: French Quarter, Bywater, and Holy Cross

Earthships outside of Taos

Due to their unique history of settlements and immigration, both towns are also extremely culturally mixed. New Orleans' history of permanent settlement was much more recent and shaped by its distinct French- Spanish colonial area from 1718 until the Louisiana purchase by the United States in 1803. Besides the obvious remnants of French, Spanish, and British settlers, many other cultures have left their mark on New Orleans culture and language over the centuries: French Canadian Cajuns, who immigrated to Louisiana in the 17th century, Africans, Creoles, refugees of the Haitian revolution from Saint-Domingue in the late 18th century, Irish, German-, Italian-, and later Vietnamese and Honduran immigrants. Good luck trying to pronounce any French sounding street names!

Even though the city of New Orleans is much younger than the Taos valley, which was settled roughly over a thousand years ago, New Orleans has been part of the US for much longer. Having been permanently inhabited over the course of a thousand years, Taos Pueblo is considered the only living Native American Community that is both a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as a National Historic Landmark. However, New Mexico, and thereby Taos, would not become part of the US until 1912! Despite its rather small size, the town of Taos is also somewhat of a tiny melting pot of Native American-, Spanish-, Mexican-, and Anglo- culture.

In a somewhat non American way, both cities also seemed to move by the beat of their own drum. For the past 100 years, their rebellious and counter culture attitude has attracted a bohemian crowd, and inspired numerous writers and artists who immortalized their chosen homes in poems, books, and paintings. I don’t know if I would have ever moved to New Orleans, if it hadn’t been for Anne Rice and her series of swampy vampire novels. And I was somewhat surprised to learn that Taos, as small as it is, was its own Moveable Feast, back in the 1920’s when the British writer D. H. Lawrence lived there, who was introduced to Taos by Mabel Dodge Luhan, a socialite, writer, and patron of the arts. Mabel, one of many remarkable women of Taos, hosted a renowned bohemian crowd, including artists and writers such as Georgia O'Keeffe and Aldous Huxley. Today, you can still visit the D. H. Lawrence ranch, or view his collection of forbidden erotic art behind a mysterious curtain at La Fonda.

Holy Trinity Church, Arroyo Secco

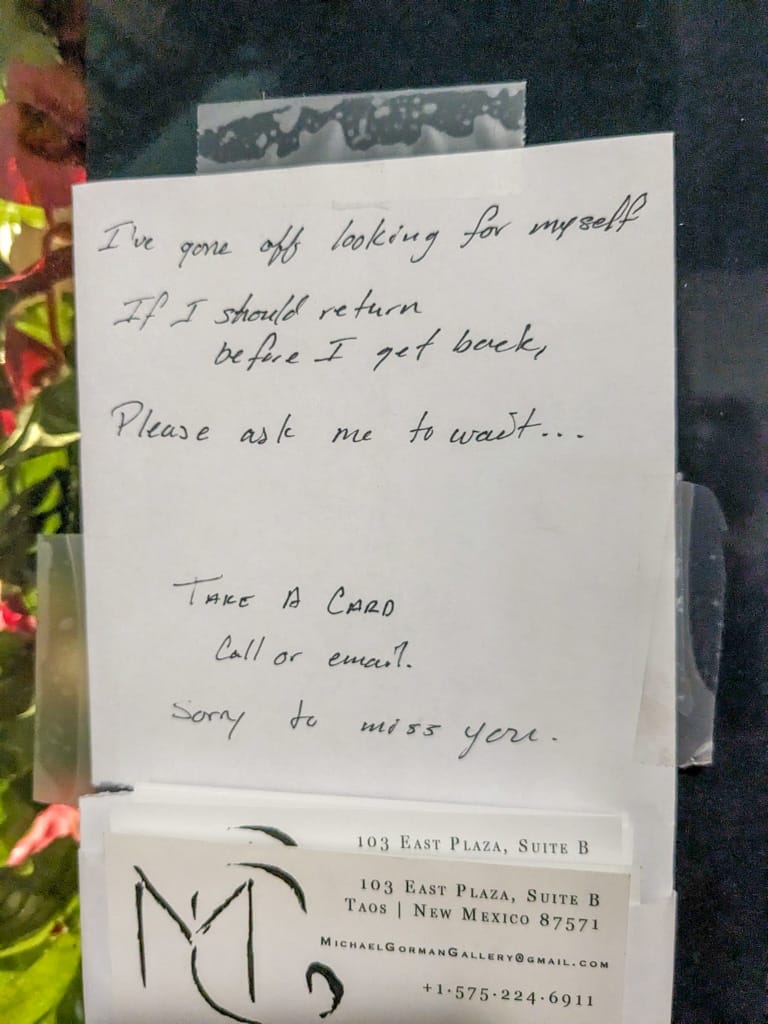

Taos is, of course, primarily known for its Native American- and local crafts. I was lucky to meet Michael Gorman, the nephew of R. C. Gorman at a private Christmas party in Santa Fe about two years ago. His uncle R.C. Gorman is sometimes referred to as “the Picasso of American Indian artists” and was the son of Carl N. Gorman, one of the original Navajo code talkers in WWII.

The grave of R.C. Gorman

The story of the Navajo code talkers in itself is fascinating: Due to the complexity of the grammar and phonetics of the unwritten Navajo language, 29 recruits were selected to develop a coded version of their language and to create a codebook of military terms modeled onto the Navy/Army Phonetic Alphabet. Even native speakers could not understand this indecipherable code, unless they underwent intensive training. These recruits would become the Marine Corps’ first all Navajo and all Indian platoon, and Platoon 382 would become known as The First 29.

Taos art and Arroyo Secco

Sacred Water and Vanishing land

In the desert, every drop of water is sacred and the people of the Taos Pueblo know that it is humans who have to adapt to nature, and not the other way around. The story of the appropriation, an undying, multigenerational fight, and later return of the fabled Blue Lake is a modern tale about displacement and the sacredness of our vital resources. According to oral traditions, passed down through countless generations, Blue Lake, or Ba Whyea, was the cradle of the Taos pueblo Indians. Their roots, religious rituals, and essential water source are connected to this place. In 1906 the US government under Theodore Roosevelt placed Blue Lake and its surrounding lands under the control of the Forest Service, proclaiming it a multi-use area, and stripping the tribe of its rights. Decades of filed suits to restore the title to the Pueblo tribe followed.

In an epic statement before congress in 1969 elder member Paul Bernal stated: “We are probably the only citizens of the United States who are required to practice our religion under a permit from the government. This is not religious freedom as it is guaranteed by the Constitution.” He further explained: “In all of its programs the Forest Service proclaims the supremacy of man over nature; we find this viewpoint contradictory to the realities of the natural world and to the nature of conservation. Our tradition and our religion require people to adapt their lives and activities to our natural surroundings so that men and nature mutually support the life common to both. The idea that man must subdue nature and bend its processes to his purposes is repugnant to our people.”

In December of 1970 Richard Nixon finally signed the law that would return the land to its rightful guardians, setting a precedent for other Native American tribes.

El Salto de Aqua and Rio Grande

In the south we can see a different but nonetheless concerning kind of displacement: rising seawater inching its way inland. A recent documentary called Lost Futures: How greed is destroying our planet by Al Jazeera shows how rural communities in Louisiana and the younger generations of deeply rooted fishermen have to deal with the rising water claiming their land.

Swamps and wetlands around New Orleans

It is heartbreaking to think that those beautiful wetlands and the historic city of New Orleans might be under water in the not so distant future, and there is little we can do to prevent nature taking its course. As Paul Bernal pointed out all those years ago, we have to respect and adapt to our natural surroundings, not the other way around.

In the end, our experience in Taos was very different from what we expected. Instead of checking out all the galleries, ongoing exhibitions, and nightly live music, we bought a used pottery wheel advertised in the local newspaper (a not so small gift from the famous mountain) and had a somewhat dramatic interaction with the local fire department. They were nice enough to come out and help us rescue our cat from a very high tree. (Yes, they actually do that). We got burritos from Mante's Chow cart and explored the surrounding 'towns' Arroyo Secco and Carson.

Like New Orleans, Taos seems to be a place where people end up who don't fit in anywhere else, and it is the creativity and character of all its inhabitants that makes this town the magical melting pot that is somehow surprisingly hard to leave.